Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of progress, particularly a critique of the idea of linear or cumulative progress in contemporary society/culture. I’ve also been reading a lot of texts/papers/letters by the founders of quantum mechanics. It’s probably not surprising, then, that the two have fused together in my mind in a strange, not altogether unsympathetic fashion.

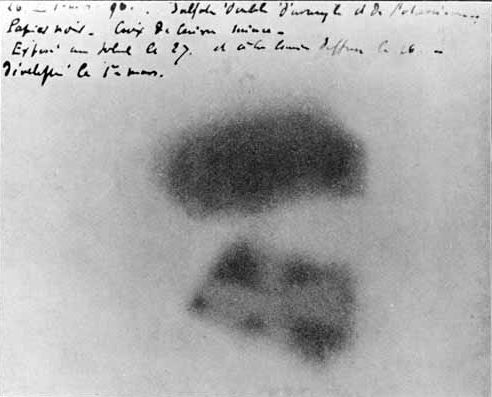

Specifically, I’ve been thinking of Heisenberg’s intuition that the particle tracks visible in Wilson’s cloud chamber images did not represent the trajectory of the particle. The particle did not have a path which could be directly observed. Thus, for Heisenberg, the idea of electron paths should not even appear in the theory. The apparent continuity of the paths is produced by many, discrete (i.e. not connected), particle collisions and ionisations. And because each random collision changes the motion of the particle in an unpredictable way, it is not possible to assign a definite location and speed at each and every point along the path.

I like this as a metaphor for a different reading of the concept of progress. Here, progress is no longer a clear trajectory moving towards some sort of perfection of behaviour or being. Rather, it’s progress understood as a series of discrete historical points, where random events cause unpredictable changes in society. Progress with its own uncertainty principle built in seems infinitely more interesting, challenging and intriguing than one which hubristically assumes human society is travelling ever-closer to the perfection of its own society/science/technology/etc.

“For the first time, therefore, I now had the opportunity to talk with Einstein himself. On the way home, he questioned me about my background, my studies with Sommerfeld. But on arrival, he at once began with a central question about the philosophical foundation of the new quantum mechanics. He pointed out to me that in my mathematical description the notion of “electron path” did not occur at all, but that in a cloud chamber the track of the electron can of course be observed directly. It seemed to him absurd to claim that there was indeed an electron path in the cloud chamber, but none in the interior of the atom. The notion of a path could not be dependent, after all, on the size of the space in which the electron’s movements were occuring. I defended myself to begin with by justifying in detail the necessity for abandoning the path concept within the interior of the atom. I pointed out that we cannot, in fact, observe such a path; what we actually record are frequencies of the light radiated by the atom, intensities and transition probabilities, but no actual path. And since it is but rational to introduce into a theory only such quantities as can be directly observed, the concept of electron paths ought not, in fact, to figure in the theory.

To my astonishment, Einstein was not at all satisfied with this argument. He thought that every theory in fact contains unobservable quantities. The principle of employing only observable quantities simply cannot be consistently carried out. And when I objected that in this I had merely been applying the type of philosophy that he, too, has made the basis of his special theory of relativity, he answered simply: “Perhaps I did use such philosophy earlier, and also wrote of it, but it is nonsense all the same.”… …He pointed out to me that the very concept of observation was itself already problematic. Every observation, so he argued, presupposes that there is an unambiguous connection known to us, between the phenomenon to be observed and the sensation which eventually penetrates into our consciousness. But we can only be sure of this connection, if we know the natural laws by which it is determined. If, however, as is obviously the case in modern atomic physics, these laws have to be called into question, then even the concept of “observation” loses its clear meaning. In that case, it is the theory which first determines what can be observed.”

– from Heisenberg’s Encounters with Einstein, published in 1983.