Nestled between forested hills and criss-crossed with clear streams, the small town of Arita can be found near the western coast of Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost island. These forests and streams, coupled with the felicitous discovery in the early 1600s of a vast supply of precious white stone, have provided Arita with its livelihood for the last 400 years: porcelain.

Down the stepped hill from the town’s revered Sueyama Shrine, whose tori archway is constructed from porcelain rather than the traditional stone, one finds a Meiji-era pottery warehouse which has been converted into a local ceramics museum. Here, just inside the entrance of the Arita Ceramic Art Museum, a large blue and white decorative dish takes pride of place. Created in the 1830s or 1840s, the dish is covered with a series of nine intricately-painted vignettes, each one narrating part of the process of making just such a dish. From quarrying the stone to clay preparation, from throwing and firing to the final glazing – even the woman who brings tea around to thirsty potters – the painstaking process of porcelain production is laid out in a lively cobalt-blue underglaze.

Although it’s likely that only two or three of these particular dishes were ever created, the same dish appears in reproduction across town in a local history museum. On an external wall one of the town’s many potteries, the dish’s central scene is recreated in large porcelain tiles. And, providing an important clue to the importance of the Dutch in the birth of Arita’s porcelain industry, another version of the dish is held in the Mesdag Collection in The Hague.

In 2016, to mark the 400-year anniversary of the porcelain industry in Arita, the Ceramic Art Museum commissioned a new version of the dish with updated scenes to reflect contemporary practices. Sitting side-by-side with its 1830’s antecedent, things haven’t changed as much as one might imagine. Certainly, labour-saving machines have automated slip casting and electric conveyor-belt kilns have replaced the wood-fired climbing kilns of old. But, in contrast to other Japanese centres of porcelain production which are fully automated (such as Tajimi in Gifu Prefecture where much of Muji’s porcelain is made), Arita makers are noted for combining mass-production methods with traditional hand painting and glazing. In one studio I visited, a painter dipped her brush in green tea before applying cobalt-blue underglaze – a practice which supposedly results in a more beautiful blue and has remained unchanged for some 200 years.

Of course, with such a high percentage of manual labour, Arita porcelain doesn’t come cheap. In Japan, tableware from the area has long been considered a luxury. In its heyday in the 1980s, large ryokans, lavish hotel resorts, placed tableware orders in the thousands and the potteries boomed. With the burst of the Japanese economic bubble in the early 1990s, many makers went out of business and Arita saw a huge drop in profits and production – from a 1992 peak of £169m worth of trade to nearer £30m in 2014.

Together with the economic challenges, there has also been a broader cultural shift in Japanese taste and social behaviour. As many of Arita’s potters stress, lifestyles have shifted ever closer to Western ways of living and eating. “There used to be a culture of inviting friends and family over for dinner,” says Shuji Hataishi, a fifth-generation potter whose family kiln is Hataman Touen. “And when people came for dinner, you wanted to serve the meal on your best tableware.” Today, Shuji explains, many younger Japanese are adopting a Western style of dining with one large plate rather than the numerous small plates of traditional cuisine fabricated by Arita potteries.

As dining culture changes, so too the average age of Arita’s consumer creeps upwards, where it now stands around 50 to 60. Given Japan’s broader preoccupation with its aging population, Arita’s potters stress a shared need to look further afield and to capture new markets in order to survive. “When I started in the industry 36 years ago, it was a time where if you made something it sold. Whatever you made, it sold,” says Shuji Yoshida, director of the Saga Ceramics Research Laboratory. “But after the bubble, the market completely dropped out and things have changed. We’re now at a moment where it feels like a new transformation, a new era.”

Of these survival strategies, the most visibly successful to date has been the Saga Prefecture’s 2016/ initiative, timed to coincide with the 400-year anniversary of ceramic production in the region. Launched in 2016 to considerable press fanfare at the Milan Furniture Fair, 2016/ comprised 400 new pieces by teams consisting of 15 international designers paired with one of Arita’s existing potteries, as well as collections by the brand’s creative directors Teruhiro Yanagihara and Scholten&Baijings.

Although I assumed the 2016/ brand was to be Arita’s porcelain Trojan Horse for breaking in to the European and American tableware market, I’m surprised to discover that wasn’t necessarily the intention. While chatting at the launch of the Saga Prefecture’s latest international collaboration, an exhibition and residency venue in Saga City called Holland House, Bas Valckx, Policy Officer for Cultural Affairs at the Dutch Embassy in Tokyo, offers a different interpretation. “If you think about the career of Issey Miyake,” Valckx says, “it wasn’t until he started showing his collections in Paris to critical acclaim that his reputation, and sales, really exploded in Japan.”

The only hitch in this plan is that, as many of the area’s potters are quick to point out, a particular style comes to the mind of a Japanese consumer when one says “Arita porcelain”. That style is well-represented in the extraordinary collection of Akihiko Shibata which has been gifted to the region’s Kyushu Ceramics Museum (500 pieces of which were also gifted to the British Museum). Here, the beautifully-subtle, often surprisingly abstract blue and white pieces of earlier Arita designs sit side-by-side with the more famous coloured enamelware later developed at the instigation of VOC merchants for the European market.

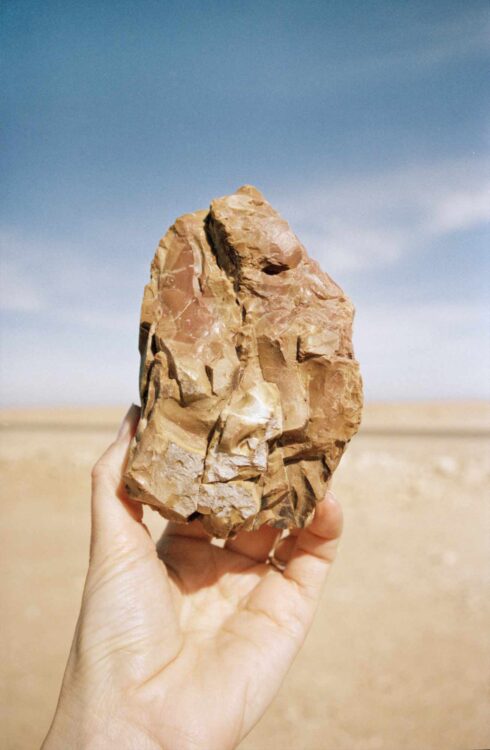

Arita’s porcelain industry was largely the result of two serendipitous events. The first was the discovery of porcelain stone – which unusually combines both ingredients necessary for porcelain production, kaolin and petunse, in one material. According to Arita’s origin myth, around 1616 Yi Sam-pyeong, Korean potter and prisoner of war (following Japanese campaigns in Korea in 1592 and 1596), discovered the stone at nearby Izumiyama Mountain. The second was the mid-17th-century destruction of China’s main centre of porcelain production, Jingdezhen, during a civil war. Following the termination of production in China, the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) turnedto Japan. Between 1653 and 1682, the VOC imported thousands of pieces of Arita porcelain to Europe through Dutch ports and hence many elaborate decorative pieces of coloured Japanese enamelware found their way into Europe’s stately homes.

The warmth of twenty-first century Arita’s feelings with respect to this Dutch connection is yet another surprise. While the potters are justifiably proud of their skills and their traditions, they are to a certain extent less confident of their abilities to understand the global market. “What was good about the historical relationship with the Dutch was that they commissioned and we fabricated,” says Koichiro Yamaguchi, head of Kin’emon Toen a tableware company founded in 1926. “We have the skills to make absolutely anything in porcelain, but sales and marketing are another set of skills which take time to develop.”

In Arita, the closest thing the potters have to a modern-day VOC is Noriyuki Momota. Momota is out of town during my visit to Arita, but he is frequently mentioned in conversation and traces of his influence are everywhere visible. Although he owns Momota-Touen Corporation, a trading company (similar to a product design manufacturer), Momota was instrumental in developing the 2016/ brand in conjunction with the Saga Prefecture. It was, in large part, his idea to bring Western designers to Arita and revive the Dutch-Japanese connection.

While many of the participating potteries suggest it is too early to tell whether Momota’s gamble with the 2016/ brand, and the considerable investment it required, will result in financial reward, they reflect positively on the subtler changes wrought by the international collaborations. “The Japanese have a very strong idea of what Arita porcelain looks like,” says Mori, factory director of Koransha, Arita’s oldest commercial pottery, founded in 1876. “But collaboration helps us understand that, regardless of aesthetic, designs fabricated here are Arita porcelain. The future of Arita is not only to preserve tradition, but to move it forward as well.”

Alongside 2016/, Saga Prefecture has been working closely with Arita potters and trading companies to test other ways of maintaining and reviving the porcelain industry. Drawing on examples provided by the European Ceramics Work Centre in the Netherlands and Jingdezhen Studio in China, Arita has recently implemented its own artist- and designer-in-residence programme. Creative Residency in Arita sees artists and designers hosted at the Saga Ceramics Research Laboratory for up to 12 weeks and paired with a pottery to develop a new artwork or product line for possible future development.

Although certain of the potteries remain sceptical as to the economic benefits of the residency project, others have embraced the programme with considerable enthusiasm. However, many admit they find it easier to work with the designers rather than the fine artists, whose methods and output they occasionally struggle to understand. But projects created by the initial cohort of residents are already being developed into mass-market collections or collectible one-offs.

In the Fukusengama factory, for example, Koji Simomura, the young and enthusiastic director of product management, demonstrates a unique spray-gun glazing technique he developed with former resident, Dutch artist Aliki van der Kruijs. The new glazing technique was born from van der Kruijs’ desire to create a porcelain pattern using drops of actual rain. “Not only are new products resulting from collaborations a way of creating new traditions in Arita,” Simomura says, “but working with someone like Aliki pushes me to use my technical knowledge in a completely different way and that can also lead to new discoveries.” The result of the collaboration, a series of plates entitled Made by Rain, are being manufactured by Fukusengama and sold as a limited edition by Dutch producer Thomas Eyck.

If it is perhaps too early to say whether Arita’s efforts to revitalise and preserve its centuries-old porcelain industry through international designers and contemporary aesthetics have been economically successful, the potters seem largely convinced of the merits of collaboration. One of my more eye-opening conversations took place with Gen Harada, director of Housengama studio, a thirteenth-generation potter and head of Arita’s labour union. Harada spoke of the labour union’s chief concerns as, not wages or working conditions as one might expect, but how to come together to find and expand Arita’s market internationally in the face of declining domestic sales. “Prior to some of the recent initiatives, Arita porcelain wasn’t well known outside of Japan,” Harada says. “It’s important to develop collaborations with artists and designers because, not only do they take the physical objects back to their home countries, but they also help to spread the knowledge of what Arita porcelain is and what our potters can do all across the world.”

Originally published in Icon, June 2018.

All photographs by François Cavelier for Icon.