A review of Han Kang’s The White Book, wrapped around a cultural history of the colour white across art, architecture, design and literature.

Originally published in Disegno Spring 2018

Snow falls. A woman walks the streets of a European city, probably Warsaw. Here, in a city almost entirely destroyed during the Second World War, she wanders amid “the white glow of stone ruins” where “the fortresses of the old quarter, the splendid palace, the lakeside villa on the outskirts where royalty once summered – all are fakes.” During a self-imposed absence from her Korean homeland, she reflects on the family stories that recount the fleeting existence of her mother’s first child who died shortly after being born. “I was told that she was a girl, with a face as white as a crescent-moon rice cake.”

It is along these two parallel axes, historical memory and personal grief, that South Korean writer Han Kang’s meditation on the colour white unfolds. Ostensibly a novel, The White Book is more a series of thematically-linked prose poems, each one with its own enigmatic title: ‘Sugar cubes’, ‘Perpetual snow’, ‘White dog’, ‘A thousand points of silver’. The sequence of short vignettes ranges across destruction and effacement, the grief of loss and finally, rebirth. Amid images of fog and melting candle wax, snow and salt and sticky white rice, Han’s narrator conflates the fate of the city with that of her long-dead sister. A person, she writes, like the city, “who had painstakingly rebuilt themselves on a foundation of fire-scoured ruins.”

That Han turns to white in her exploration of memory, being and grief is perhaps no surprise: Koreans are known as baek yi minjok, the “white–clad people”. White has been an emblematic, symbolically-important colour in many cultures, but perhaps especially so in Korea. Unlike its near neighbour China, where white holds many of the same, sinister associations as that of black in Western cultures, white for Koreans has traditionally signified innocence, nobility and respect for the heavens. Consequently, as Bong-Ha Seo writes in the Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles, historically, Koreans wore white “all throughout their lives: from the moment of their birth until their death.” In the 19th century, R. V. Laguerie, a French reporter for L’Illustration, visited Korea and later wrote in his 1898 book, La Coree, that “everyone walked slowly and heavily, all in white.” Following the Japanese-imposed Protectorate of 1905, the already-well-established connection between Koreans and white dress took on newly-charged revolutionary undertones, according to Bong-Ha. When the Japanese banned Koreans from wearing white-coloured clothing, “the Koreans wore white clothes more than ever,” writes Bong-Ha. “White clothing united all Koreans into one nation, regardless or their class or occupation, symbolizing Koreans’ anti-Japan movement.”

In its use of meditations on a single colour as a lens through which to begin to approach personal grief, Han’s White Book bears some resemblance to writer Maggie Nelson’s 2009 Bluets. Where Nelson’s openly autobiographical Bluets displays both rawer emotion and a seemingly stronger personal attachment to blue, Han’s more oblique approach to white and to grief is a quieter, more plaintive take on the theme. If Nelson’s blue is an earth-bound pile of powdered ultramarine pigment that can change the world (“You might want to reach out and disturb the pile of pigment, for example, first staining your fingers with it, then staining the world”), Han’s white is the “vast, soundless undulation between this world and the next”.

White for Han, as for the Japanese graphic designer Kenya Hara, is something elemental and so pure that it is not altogether of this world. “White is the most singular and vivid image that arises from the centre of chaos,” wrote Hara his 2010 book, White. For Hara, as for Han, white is a kind of whispered fragment of a barely-remembered dream: “Life comes into this world wearing white, but it begins to acquire color the instant it assumes concrete form and touches the earth, like a yellow chick emerging from a white egg. White can never be made manifest in the real world. We may feel that we have come into contact with white, but that is just an illusion. In the real world, white is always contaminated and impure.”

And yet, it is here, at the intersection of purity and impurity where white so often runs into trouble. Yes, white is the “swaddling bands, salt and moon” of Han’s narrator’s list of, perhaps elemental, perhaps comforting, white things. But white is also the misinformed cultural superiority of 18th-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s reading of the white of ancient statues. White is the troubling argument for the biological superiority of “whites”, posited by French writer Arthur de Gobineau in his 1853 ‘Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines’.Admittedly, white is not the only colour with tricky cultural connotations and the argument that colours are more importantly understood as perceptual and cultural rather than purely scientific phenomena is one expressed by Goethe in his Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colours). Refuting Newton’s notion that colour was determined purely by light, Goethe attempted to approach a kind of scientific analysis of colour as a phenomena shaped by perception, including moral associations. “Since colour occupies so important a place in the series of elementary phenomena,” he wrote, “we shall not be surprised to find that its effects are at all times decided and significant, and that they are immediately associated with the emotions of the mind. ” After all, scarlet in the book of Revelation is not merely visible light with a wavelength of 625 – 740 nanometres; it is the shade of the harlot and of the beast. White, unsurprisingly, is the colour of Christ.

Indeed, according to University of Pennsylvania historian Kathleen Brown, this union of white and purity – specifically in Western culture – likely has its roots in religion. In an interview with Nautilus magazine, Brown explained that, “historically, white is one of the ways men of the cloth signified their calling.” These associations with religious purity ultimately evolved into bodily purity, a pre-occupation which continues in today’s obsession with ever-whiter teeth and skin-whitening products.

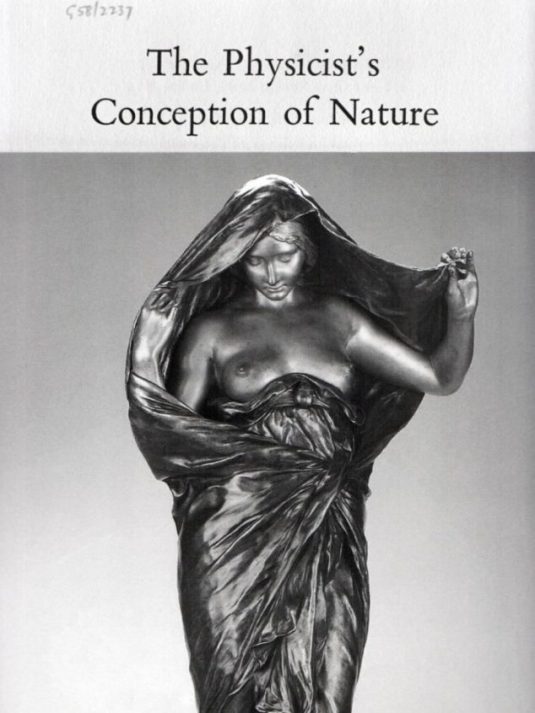

Similar associations between purity and white were key arguments in Winckelmann’s writings. At a time marked by the rediscoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum and a vogue for all things ancient Rome, Winckelmann’s 1764 Geschichte der Kunst des Althertums, revolutionised the understanding of stylistic changes in Greco-Roman art. And yet, one of Winckelmann’s most influential arguments helped to bury the excesses of Baroque aesthetics in favour of the “edle Einfalt und stille Grösse” (noble simplicity and quiet grandeur) of neoclassicism. Rediscovered after being buried or weathered or otherwise aged, the marble statues and sculptures of classical antiquity were taken to have originally existed as they were later rediscovered: white. Winckelmann, like others before him, chose to view the unadorned stone figures as pure, almost austere, forms. “The whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well,” he wrote. “Colour contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty. Colour should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not [colour] but structure that constitutes its essence.”

Although subsequent research has demonstrated that many sculptures, statues and temple friezes of classical antiquity were in fact painted in a variety of bold, bright colours, the accidental fact of the later discovery of white statues shaped generations of Western cultural aesthetics. These are aesthetics that won’t be easily overturned. When archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann’s garishly-coloured copies of antique statuary, first appearing at Munich’s famed Glyptothek in the 2003 Gods in Color exhibition, went on tour across Europe and the US, they were met with shock, and occasionally outrage. “You have completely ruined the image we had of antiquity, ” summarized the director of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens of certain visitors’ reactions to Gods in Color when it toured there in 2007. Removing the noble purity of white from the artistic works of our Greek and Roman forefathers was also somehow tantamount to removing the noble purity of every intervening cultural endeavour which followed. It was Bernini’s David painted green, red and gold. In other words, it was seen as a disaster, a kind of destruction.

By contrast, the image of cultural destruction as a glittering whiteness is deployed by Han to powerful effect in her description of the city of Warsaw in 1945: “I saw some footage of this city, taken by a US military aircraft in the spring of 1945. […] The subtitles said that over a period of six months, starting in October 1944, 95 per cent of the city was obliterated. […] When the film opened, the city seen from far above appeared as though mantled with snow. A grey-white sheet of snow or ice on which a light dusting of soot has settled, sullying it with dappled stains. The plane reduced its altitude, and the city’s visage sharpened. There was no snow covering it, no soot-streaked ice. The buildings had been smashed to pieces, literally pulverised. Above the white glow of stone ruins were blackened flecks as far as the eye could see…”

In 1925, 20 years before Warsaw was reduced to glowing white rubble, Le Corbusier declared, in inimitable fashion, that whitewashed walls had a spiritual and moral cleansing power. His Law of Ripolin (so-called after the popular brand of household paint) declared that every citizen should “replace his hangings, his damasks, his wall-papers, his stencils, with a plain coat of white ripolin. His home is made clean […] Everything is shown as it is. Then comes inner cleanness for the course adopted leads to refusal to allow anything which is not correct.” Although more frequently appearing in his rhetoric than in his practice, white for Le Corbusier and his contemporaries was a portal to a renewed era of humanity; with a single sweep of a paint brush, its perceived rationality, morality and functionality could erase the tarnish of the past.

If Corbusier’s and modernism’s obsession with the formal purity, moral rectitude and sheer cleanliness of white was later called into question within architecture and design (a wonderful anecdote in Jeremy Till’s Architecture Depends has James Joyce saying, “You don’t know how wonderful dirt is” in riposte to Sigfried Giedion’s praise of some Marcel Breuer houses), in the West, at least, white’s symbolic hold continues to reign over birth, marriage and dentistry.

In Japan, Korea and certain other East Asian countries, the colour’s associations with purity and innocence and nobility of spirit continue to hold great importance in cultural rituals, artistic aesthetics and spiritualism. Han’s The White Book thus draws on a tradition of white which retains a sense of the colour as a symbol for the fragility of life and the weltschmerz of things too good for this world, a tradition beautifully encapsulated in a short 15th-century poem by Korean poet Song Kan (1427-1456):

Mountains rise over mountains and smoke from valleys;

The dust of the world can never touch the white gulls.

The old fisherman is by no means disinterested;

In his boat he owns the moon over the west river.

Echoes of this ideal of white as an elegy for the transient beauty of life – surely a more palatable cultural association than de Gobineau’s white as racial superiority or Le Corbusier’s tightly-bound tyrannical white or Winckelmann’s white as expression of perfection of form – permeate Han’s narrative. Her unnamed narrator’s meditations on her ghostly twin, her too-fragile-for-this-world sister, and her reflections on the destruction done by men to each other and themselves are filtered through white. Not Corbusier’s white, nor Winckelmann’s, but the “billowing whiteness within us” which recognises the inviolate in “our encounters with objects so pristine [and] never fails to leave us moved”.

As Han writes, “there are times when the crisp white of freshly laundered bed linen can seem to speak. When that pure-cotton fabric grazes her bare flesh, just there, it seems to tell her something. You are a noble person. Your sleep is clean, and the fact of your living is nothing to be ashamed of.”